I first met Francis Glatz just over a year ago when I rang him up to ask him if he had any spare parts for my ATZ mountain bike forks. He immediately invited me down to his amazing workshop nestled in the Jura Mountains in Switzerland so he could have a look at my forks (there’s a link at the bottom of this post about my Cilo MTB fitted with Francis’ ATZ forks). I quickly realised that I had just met one of the world’s true innovators, solution finder and great personality. Francis agreed immediately to do this interview when I mentioned it, and whilst it captures some really interesting stuff about Francis, it really is just the tip of the information iceberg, because I reckon there’s a good book to be written about this man. Anyway, for now, here’s an insight into Francis and his work.

Q: How would you introduce yourself to someone who has never heard about you or met you before?

A: I am Francis Glatz, born in 1946. I am Swiss and one quarter Italian, my star sign is the fish, and from birth, I have been extremely curious. My work is a pleasure as I have the freedom to think through ideas and challenges, and apply my curiosity to find solutions that provide a fit-for-purpose result.

Q: You once said to me: As an innovator, your objective is to always find simple solutions to complex problems, so at what age did you start your journey as an innovator and what were the early challenges that you tackled?

A: I started very young. I was 4 years old when my grandfather put me on a chair in front of the machine. I still remember the smell of the oil being burned by the hot steel shavings. My current workshop has a similar atmosphere.

As a child, I used to disassemble and open up products, parts and machines that were not working so I could understand how to fix them. This was the best university for me. Today, people are less interested in doing this as you can’t even go down to the town dump to get something like an old alternator to understand how it works. Just reading a book about alternators doesn’t help in understanding them if you don’t actually have one to disassemble. There is no access to any industrial trash for people to learn and experiment with nowadays. This means that if you have to buy a used part to be able to understand it, you lose the fun of developing knowledge and creativity.

Q: What stimulates you to you continue to come up with fresh, new ideas?

A: The stimulation does not always come from myself. I find that a lot of ideas for something come from other people and I have the ability to bring these ideas to a reality, and which works really well. I also get ideas myself and based on everyday challenges. For example, I have a problem with my eyes and I need to put some solution in them regularly from a little eye-drops bottle. This isn’t easy, as I was not getting the solution into my eyes accurately, so I made some metal framed spectacles that will hold the little plastic bottle directly over the eye. The device also tells me when the frames are at the right angle by the little sliding ball. When the ball moves along the rod to the bridge of my nose, I can then squeeze the bottle gently to get the solution in my eyes. It works perfectly and also at night in the dark, because when I hear the little ball hit the frame, I know that the bottle is in the right position. When I went to the hospital for an appointment, I took this idea with me and in 30 seconds, all of the nurses were gathered around and amazed at my idea.

Like all of my solutions, this one is very simple, and importantly, I also always think about how ideas like this can be used globally. When I consider an idea, I have the ability to instinctively think about the materials, the process, the right machines to use, the testing, the price and the global use of a final product or solution. Usually, if a solution to a problem is complicated, it will be expensive, so my goal is to make great quality, affordable and simple solutions to ideas and challenges. If I don’t get a good feeling inside of me about one of my ideas, it isn’t the final result and can be made better.

Q: Have you always worked as an independent business owner or have you worked for big organisations as well?

A: I have worked in places from the industrial machining sector to the watch industry and I have usually spent about 3 years at a company to learn fast, as it was always very interesting, but I didn’t want to stay in a big factory for a long time. I actually like working on my own and from an early age, have always been independent. However, I needed to work to feed the family whilst I gained the skills that would enable me to work on my own and get enough income, so working for the big companies in my early career was important. I did the work for the company first, and later in the evening, I did work for myself as I experimented and learnt.

Q: Tell me about this amazing building that we are in now.

A: I designed and built it in 2004. I had previously been working out of a small workshop and had just invented a way to manufacture a small component for the automotive industry which was fitted inside the speedometers of cars made by BMW, VW-Audi, Mercedes and Toyota. When the quality audit teams from these big companies came to see me, they advised me that I needed a much better and professional workshop.

Whilst I was building this workshop, I had to keep manufacturing the small automotive parts and I even fitted the machine that made them into the back of my van so that when I went to the restaurant in the evening, I parked the van outside and the machine was still producing the parts whilst I was eating.

I bought the land for the workshop and it took 2 years to complete the building, which houses all of my machines as well as a very modern living space on the second floor, and with views across the Swiss countryside. The whole building is a great example of a solution to a problem, which was to create a world class working and living space.

Q: Which two-wheeled work came first? Motorcycles or bicycles?

A: Motorcycles came first. I always loved motocross and in 1974, I bought a KTM 250cc motocross bike, which had great power, but the rear suspension eventually broke and I couldn’t afford to buy new shock absorbers, so I decided to learn all about suspension systems. Whilst talking to a local sidecar road racer, I got the idea from him to build a shock absorber without the traditional coil over spring. I then produced and developed my own air and oil shock absorbers for all road racing motorcycles for the next 20 years, and under my own ATZ brand. The name ATZ is from the last three letters of my surname.

I made shock absorbers for motocross and trials bikes, racing sidecars as well as Grand Prix and Endurance road racing bikes. In 1981, the Kawasaki France Endurance racing team used my shock absorbers as well as the French hub-centre steered Elf Project road racers. I worked at the Grand Prix races for 8 years with some of the world’s top racers like the multiple world sidecar racing champion, Rolf Biland as well as other famous racers of the time like Philippe Coulon.

Q: What has been your single, biggest learning in your life as an engineering innovator?

A: My biggest learning is that ‘you think you know it, but you never know it’, so I always correct people when I hear them say ‘I know’ when they’ve been told something, because a lot of the time, they don’t know. If you say ‘I know’, you will never really look into a subject in any great depth, and which will allow you to learn and think differently. In reality, we never really know everything. Lots of people naturally say ‘I know’, but actually, the only thing they do know, is that they don’t know.

Q: For all of the aspiring inventors and innovators out there, what one piece of advice would you give to them?

A: The first thing is, inventing is not a job. The second thing is that when you develop a product, you must consider how the person will use it so that it can provide performance, be repairable and not just another throw-away product. A lot of products that we see today are only designed and made to get a quick monetary return and they are not designed for ultimate fit-for-purpose use or for the long term, and I think this is catastrophic for the world. We will not save the planet whilst products and solutions are being created just to make money, as they will only be trash in the short term.

Q: If you could only listen to one piece of music or song whilst working in your workshop, what would it be and why?

A: I would listen to the great Norwegian jazz saxophonist, Jan Garbarek, as he is the master of just being able to improvise and to create amazing music.

Q: You invented lots of domestic solutions and products. Which one do you use regularly and works really well?

A: The electric coffee grinding machine, which I use every day. That question was too easy!

Q: Talking about bicycles again, what got you into bicycle design?

A: I decided that I had had enough of the Grand Prix motorcycle work after 8 years of travelling and decided to moved onto bicycles to apply similar suspension ideas in 1986. I was selling my suspension to the racers for a competitive price, but I was also doing the servicing. However, another big suspension producer started giving the riders shock absorbers for free, which weren’t as good, and if you give riders things for free, they’ll usually take them, even if they are not as good as what they had been previously paying for.

I had read an article by Gary Fisher about mountain biking (which I salute by the way) and I had my own idea to design, manufacture and sell a complete Swiss mountain bike. I had seen the new mountain biking trend and decided that I could apply my suspension technology and thinking to a bicycle. I did some research and I visited two local bicycle shops and asked them both if they thought mountain biking was just a short term trend or if it was a cycling sector of the future. The first shop owner said that the trend would be out of fashion by the end of the year and the other one said that mountain biking will be the long term future, so I started to build my first bike.

I made about 35 bikes of the first design, which had pressed aluminium frames, although all of them were slightly different as the design developed. One thing I considered whilst designing the first aluminium bikes, is that the second generation of the the design would be made out of carbon fibre. The sale of the first 35 bikes went to pay for the manufacture of the second design of carbon fibre bikes. I learnt how to work with carbon fibre myself and with help from the motorcycle racers, who were using carbon fibre in racing. I made the moulds, laid the carbon fabric, understood the resins and manufactured them. The carbon suspension fork was the first thing I made on the bike.

Q: How did you design your bikes and how many different designs have you made?

A: I actually designed my bikes on a 1-to-1 scale. I went down to the local newspaper printers and asked them for some of the wide paper that they printed newspapers on and then I drew it at full scale and put the parts on the paper design to ensure a complete match and fitting. This way, it also allowed me to make changes to the design as I improved it.

I have made several designs, and one of the first bikes I designed was for a long distance German cyclist who had already ridden around the world, but always got bad blisters on his hands. I made a full suspension bike for him out of aluminium and he rode it around the world without any blisters or issues with the bike. I also made the downhill bikes for the Swiss downhill rider, Philippe Perakis. My full suspension bikes even had suspension lock-out devices!

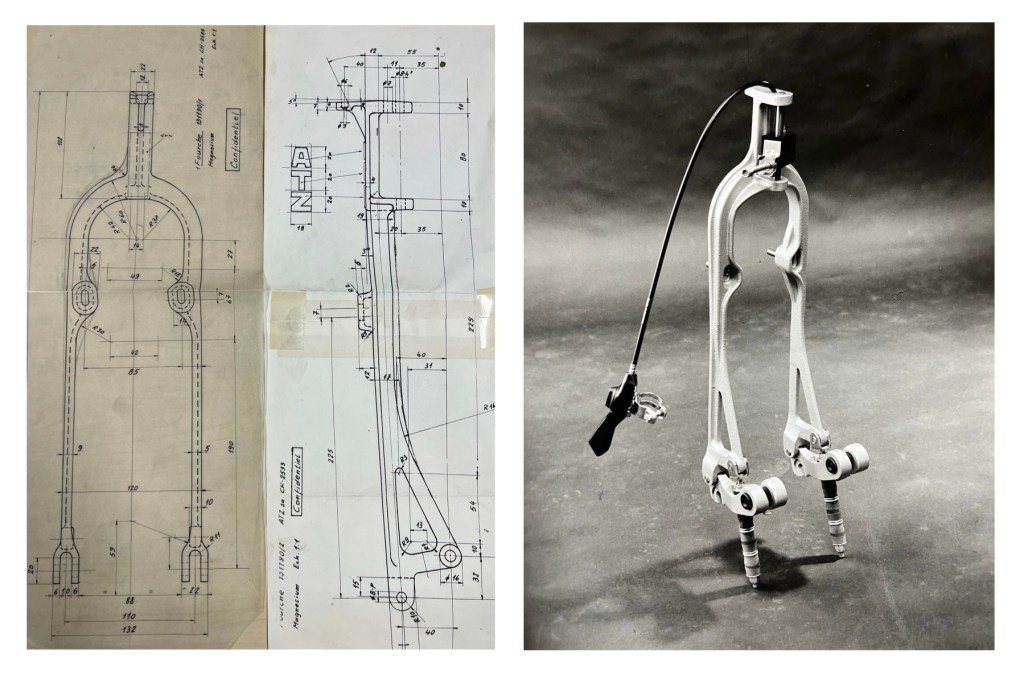

Q: What made you settle on the design for the ATZ elastomer suspension fork rather than a motorcycle style sliding stanchion type of fork?

A: I knew from my motorcycle suspension experience that a sliding stanchion had too much friction in the sliding tubes for a bicycle’s weight at that time, and that a cyclist needed a very sensitive and faster damping method, so I decided to use elastomers in the design instead, and this was a critical part of the design criteria.

Q: The first ATZ elastomer forks were carbon, so why did you eventually manufacture the forks in magnesium?

A: I took my new forks to the head of the Swiss, Cilo Cycles company to show him. He said that he would take 500 of them and sell them as a performance upgrade for the new Cilo mountain bikes and through his big European dealer network. I explained that I didn’t have any money to start production and asked him for 80,000 Swiss Francs, which he agreed to, and on the basis that delivery would start in 2 months. We also agreed that Cilo would have exclusivity to sell the new suspension forks for 1 year. All of this was agreed within a 20 minute conversation.

I realised when I got home from the meeting with Cilo Cycles that I could not manufacture the carbon forks in that volume within 2 months, so I had to re-think my design. I decided that getting the forks cast in magnesium would be of equal performance to the carbon design, so I drove to Italy to the company that made the magnesium wheels for Ferrari. I created a design on paper and showed it to the boss of the company who was looking a bit depressed when I met him, as he had no work in the factory. He said that he could cast the forks, but needed a wooden model to make the moulds, as they were all cast in sand. He told me that there was a great carpenter in the next village that could make a wooden model. I took it to the carpenter and he made it in 10 days.

The factory then cast me 4 prototypes, which I then took back to Switzerland for testing. When I tested the forks, I realised that when the front brakes were applied, the forks flexed outwards. I designed some additional bracing for the forks and the carpenter made a new model. I also got these magnesium forks heat treated so that they were much stronger. The casting company made me 500 forks and in 2 months, I went back to Cilo with the forks, and even including the brochures about them.

The Cilo forks were painted yellow to match the bike frame colours and I supported the Cilo racing team with fitting and servicing the forks. Philippe Parakis was a good tester for the forks because he was a fast rider. After the first year with the Cilo forks, I changed the colour of them to white and sold them under the ATZ brand.

Q: How many of the magnesium forks have you sold to date?

A: Approximately 2500.

Q: If anyone out there has some of your ATZ forks or suspension, can they send them to you for servicing?

A: No. I don’t have the energy or time to service forks. However, there are a lot of my ATZ motorcycle shock absorbers still in use and working well, but it would be good to hand over the ATZ suspension business to a young and interested talent, who can develop the suspension further and can service all of the ATZ systems out in the world. I don’t even have a website for my ATZ products.

Q: You have made mountain bike forks and frames, what other parts have you designed and made?

A: I was one of the first people to put a disc brake on a bicycle. It was a cable operated mechanical caliper and made by Grimeca in Bologna, Italy. The actual disc of the brake came from a wheelchair and I made the centre spider and hub for the disc myself out of carbon fibre to fit the bike. It was a fully floating rear disc brake as well, which also came from my motorcycle experience.

Q: Favourite food and why is it your favourite?

A: Fresh fish from the sea or the lake, and because the fish is my star sign.

Q: Favourite type of drink; Beer, wine, spirits or all 3?

A: Locally produced red wine, and a teardrop of Scotch whisky in vanilla ice cream.

Q: What projects are you working on now?

A: I cannot share every idea, but the projects range from designing a new heating system for my girlfriend’s house to a portable, electric ski lift.

Q: Have you ever shared your life and work with students studying design at universities or schools?

A: A student from a Swiss university once completed a thesis for his engineering degree based on the principles of my motorcycle suspension.

Q: Do you have any new ideas for a bicycle?

A: Yes. I have an idea from a long time ago to build a completely different type of bicycle. Unfortunately, I cannot share any more details here😉.

Q: What has been the one design or solution that was the most successful and why was it successful?

A: The most successful designs are the ones that get to the market. If a design doesn’t function, it does not get to market. I had a recent phone call from a man in Geneva who has a racing motorcycle with my ATZ shock absorber in it and he told me that his bike was 25 years old, ridden regularly and is working perfectly. He asked me if he needed to put any air in the shock absorber! That shock absorber is 25 years old and isn’t leaking any air or oil. An example like this tells me that both my product design and manufacture was successful.

Q: You have a big workshop full of great machines and tools. Which is your favourite machine or tool and why?

A: I love all of them. They are like people, all different. Actually, I like the machine which creates me the biggest challenges to understand how it works, and so I can get it to do what I want it to do. Machines don’t talk, so you have to work hard to understand them. The more complicated, the better for me.

The machine which fits my criteria above is my Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM) piece of equipment. To cut something, it takes a lot of thinking to set it up. It is easy for me to understand a fully mechanical machine, but this one is very different in its use of electricity for cutting and in the programming of its electronics.

If you want to get in touch with Francis directly, his email address is: [email protected]

Here’s the first post I wrote about Francis’ ATZ forks that I have fitted to my Cilo MTB, and which had some of the original specification elastomers recently fitted by Francis himself https://diaryofacyclingnobody.com/elastomers-for-my-atz-cilo/

Photos 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11 & 12 courtesy of Francis Glatz

All other photos taken by the Author

Cool interview. I would like to have learned about where he grew up, what type of apprenticeship he made.

Thanx! That additional information will be in the book……whenever it gets written??

Excellent story, I knew of the shocks, don’t believe I ever used them. Rebuilding his shocks, nice retirement project for you.

Thanks for the suggestion, but I don’t think I’ll have time?